by Paul L. Heck (July 21, 2014)

This essay is no easy read. Brace yourself and be bold.

It may not be for everyone. Reader discretion is advised.

A friend asked me some weeks ago, “How does the Holy Spirit work in Islam?” This friend spends a lot of time thinking about Christianity and its meaning for contemporary life. And today, it no longer makes sense, if it ever did, to say that God is with some and not with others.

It is this that prompted his question. In asking about the Holy Spirit in Islam, he wants to know how God is with Muslims; and for him, as a Christian, it makes sense to pose the question in terms of the Holy Spirit. After all, it is in terms of the Holy Spirit that Christians understand God to be present to His creation.

But not all would refer to the Holy Spirit in thinking about other peoples and their encounter with God. Muslims would not frame the question in terms of the Holy Spirit. They might refer to the divinely oriented nature with which God created humans and which prophets embody most completely, especially Abraham and Muhammad. In this view, others—Jews, Christians, Atheists—have beliefs that detract from the way our human nature in its original condition works to orient us to God, but this nature remains intact in some measure even when one is not a Muslim. Non-Muslims can thus live good lives even without the truth of Islam, though Muslims would say it is better for them to embrace it. This would be but one way in which Muslims view others.

The point is that religions have different ways of making sense of other believers. To be sure, some condemn others outright on the basis of their beliefs and doctrines even apart from their behavior. You believe that! You are God’s enemy! You can’t possibly be good! Here, all that matters is one’s communal identity irrespective of one’s morals and whether or not one is a good person and kindly towards all.

However, believers know that scripture is not so condemnatory. It speaks of divine providence extending to all peoples. God is the creator of all. He thus cares for creation entire. Believers across faith traditions acknowledge the universality of God’s interest in humanity. Thus, even apart from beliefs, other peoples are not to be condemned. They, too, fall under the shadow of God’s all-encompassing care.

But not all peoples speak of God’s all-encompassing care in terms of the Holy Spirit. It is a Christian way of thinking. Still, one need not be a Christian to benefit from discussion of the Holy Spirit and its relation to other faith communities. After all, spiritual realities are something we all experience. In addition to physical senses, we also have spiritual senses by which we grasp spiritual realities beyond physical ones. Not all want to admit this. Scientific evidence shows that people would prefer to self-inflict the pain of electric shocks onto their body rather than think quietly.

The University of Virginia conducted the experiment, and the results were published in July 2014. People prefer inflicting physical pain onto themselves rather than thinking quietly for fifteen minutes. Fifteen minutes! What does this mean? The participants were stripped of all electronic devices and placed in a bare laboratory with nothing but a button in front of them. This button, if pushed, delivered electric shocks to their bodies. Most pushed it. They simply could not sit quietly for fifteen minutes without wanting distraction, and a painful distraction is better than no distraction at all. But what were they distracting themselves from? And why? The short answer is this: They were distracting themselves from themselves—from having to consider the movements within themselves that silence would force them to consider.

Why? Are they afraid of what they will discover there—that at the core of their being stands nothing at all? It is difficult to admit this. More precisely, it is painful. The pain is not physical but is harder to endure than physical pain, so much so that one would happily avoid it by inflicting electric shocks upon oneself. Better that than the pain of having to see how completely deceived one is about the reality of one’s own being. To sit quietly, one would have to think about it, and it’s too painful, and so we opt for distractions, any distraction, even the distraction of physical pain.

But we miss the prize. In fleeing from the pain that comes with the recognition of our own nothingness, we fail to see what lies just over the horizon. The anxiety we feel at seeing the nothingness that stands at the basis of our existence is just a temporary stage—quite brief—in the greater process of spiritual attunement.

There’s a lot to discuss here, but let me state it baldly. In the first fifteen minutes of contemplation, one is stricken with a kind of self-loathing. This is the result of seeing that one came from nothingness and will return to nothingness and that therefore nothing stands at the core of one’s being. However, in the second fifteen minutes, one discovers a joy that overcomes the pain of realizing that one is nothing. One is struck with joy at the fact that life is sheer gift. It is not something we have earned. We have been graced with life.

The process of spiritual attunement is not instantaneous. It takes a bit of time and a lot of fortitude to endure the first fifteen minutes. But a shift occurs from anxiety to delight. We all know that much insight can be gained from contemplating the depths of our being, but the first stage is the hurdle. We’d rather just push the button.

Be that as it may, our point here is that we all have spiritual senses by which to explore the depths of our inner life, even if it is painful to use them for fifteen short minutes. And yet discussion of the Holy Spirit, even if a Christian discussion, has something to offer all. A discussion of the Holy Spirit necessarily involves the spiritual senses. It is through the spiritual senses that one comes to know the Holy Spirit. (One could never rationally argue one’s way there.) Thus, if we are all possessed of spiritual senses, we can all be edified by a discussion that involves them even if it does not start from the language of one’s own tradition.

So it’s less painful to live in ignorance of oneself but ultimately much less rewarding.

To begin: One sees in the history of Christianity two ways of thinking about the activity of the Holy Spirit. There is the gift of creation. (One might call it general grace.) And there is the gift of redemption. (One might call it special grace.) Both are acts of God. One might even refer to them as two ways in which God makes Himself known, that is, two kinds of revelation. By reflecting on creation, we can know that it has a creator. Not all draw this conclusion, but over the centuries many have. Redemption goes further. It is not simply about a creation that comes from nothingness and will return to nothingness. It is rather about a creation that God in his loving kindness has redeemed from its nothingness and given a share of life with Him. The fact of creation alone might suggest that God is kind. After all, why would He bring creatures into being out of nothingness? That was awfully kind of Him to bring us into existence, wasn’t it? But we might still have doubts. OK, He created us, but look at how bad everything is. Is He really so kind? Redemption makes it clear. God’s action to redeem us confirms that His essential characteristic is loving kindness since in redeeming us He makes manifest His desire to give us life and to give it to us in abundance. In this way, he demonstrates that the mess we’ve made in this world is not His will for us.

We will speak more about redemption in a moment, but there’s another point to be made about creation at this point. Creation has two sides. It has a material side. This is obvious. But it also has a spiritual side. This is less obvious but no less evident. As noted above, in addition to our physical senses, we have spiritual senses. By using them we can detect a world within ourselves. Some of it is ugly, even terrifying, and some of it is beautiful and even gives us pleasure of a kind. Exploration of our inner geography helps us see what gives us real delight as opposed to what does not sustain us over time. It allows us to know who we really are and what we really want—and to pursue it.

The point is that even without the knowledge of God’s redemptive activity, humans, all humans, have access to God’s guidance simply by virtue of being human. They can know, without any special grace from God, what gives them life in a spiritual and not solely biological sense: what sustains them beyond bread and fancy cars alone. Christians are not averse to speaking of this as guidance from the Holy Spirit even if one need not go to church in order to have it. Of course, Christians would claim that even greater spiritual delight is to be had from attending church, but they are also ready to speak of God’s grace at work in creation. All have spiritual senses by which to experience spiritual realities. The spiritual senses can be misused. Still, within us lies a great mystery attracting us to want to know the font of loving kindness that brought us into being and that is at play in the depths of our very souls. That is the grace of creation. Christians happily acknowledge it as one way the Holy Spirit operates.

But there’s something more. There is a history of God living with His people. What does it mean for God to live with His people? It’s a complex subject, but it involves more than just speaking of God as creator. It means not only that God creates. It means that God enters into friendship with His creation. But creation has to be made ready for this friendship. It must be redeemed from its nothingness and all that that means. Here, the Holy Spirit works not simply in terms of the spiritual senses with which God endowed humans at creation. Rather, it works at God’s initiative. It is not so much about the spiritual ability of humans but rather God’s intervention into the human condition.

Here, we are talking about special grace. When it comes to redemption, the Holy Spirit works not only to guide creation but to introduce it into a life of friendship with God. For that to happen, humanity has to be redeemed, and that’s the task of the Holy Spirit. For Christians, the story of redemption began long ago. As narrated in the Hebrew Bible, the story speaks of God dwelling amidst the Israelites. He is present to them not only as creator but even more so as the lord of life. It is because of His presence in a special way amidst the people that they have life. Separation from His presence would mean death. The Israelites, for their part, had a knack for going astray. They were quick to turn their backs on the Lord dwelling in their midst. Given their waywardness, God their Lord might have abandoned them or even destroyed them, and the biblical narrative sometimes suggests He is ready to do so. But He repeatedly opts instead to redeem the Israelites, making it possible for them to continue to dwell in His presence. His persistent willingness to redeem the Israelites so that they might enjoy life with Him demonstrates the boundlessness of His loving kindness.

For Christians, the story of God’s loving kindness reaches its climax in the cross. What’s the cross all about? The question is not easily answered. Suffice it to say that Christians see the cross as the place of God’s redemptive sacrifice on behalf of creation. As the priests of the Israelites undertook acts of redemptive sacrifice in the ancient temple on behalf of the people, similarly, in the cross, God undertakes a singular act of redemptive sacrifice on behalf of creation—renewing it and making it ready for life in His presence. In this sense, the cross is the fulfillment of the story of redemption. From the cross the Holy Spirit is poured out in a powerful way onto creation to recreate—and not merely to guide—it, making it ready for a life of friendship with God—redeeming it from the nothingness that would be its lot if creation remained but creation and was not remade for the sake of friendship with God.

All of this is to speak of the lordship of God in the sense that Christians understand it. There is the divinity of God. And there is the lordship of God. The divinity of God. The lordship of God. The two concepts are related, but they’re not quite the same thing. The divinity of God is quite beyond the capacity of the mind to grasp by its own powers. The lordship of God is another matter. It is the way God makes Himself manifest to humanity in both creation and redemption. To speak of the lordship of God is to speak of God’s action, which for Christians falls generally into the two categories of creation and redemption. In creation, God says to His creation, “I give you existence.” In redemption, God says to it, “I give you new life with Me.” This is what Christians mean by the lordship of God. God’s lordship is made manifest in many ways but is disclosed in a special way in God’s redemptive action in the cross. Thus is God’s lordship dynamically active in the cross, making all things new. It is through the redemptive sacrifice of the cross that God ushers all things into life in His presence, since it is from the cross that the Holy Spirit is poured out onto creation.

This gave a whole new meaning to the concept of temple. For Christians, it is no earthly building that houses the Holy Spirit. The human being is the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit in a special way. Christians know this because of the cross. The cross is where the Body of Christ served as God’s temple, that is, the place where God undertook His singular act of redemptive sacrifice on behalf of His creation—and thus the place where the Holy Spirit was poured out onto creation. The apostles were witnesses to all this, and Christians today also witness this divine action by participating in the Eucharist that serves to unite them to the Body of Christ.

Where has all this gotten us? The Body of Christ is the temple of the Holy Spirit, but for Christians the Body of Christ is no historical artifact. It is something they live. The Body of Christ is now represented in the Church, that is, the community of the faithful. When the community of the faithful comes together to celebrate the Eucharist, they receive the Holy Spirit. In this sense, the Church becomes the Body of Christ, the place where the Holy Spirit is poured out onto creation. So, there is a close link between the Body of Christ and what goes on when the community of the faithful gathers to participate in the Body of Christ through the celebration of the Eucharist. It is in this sense that the body of Jesus of Nazareth—crucified and buried and raised to God—discloses to us the true meaning of our own bodies. Why do we have a body? Through incorporation into the Body of Christ, our bodies are redeemed from nothingness and are remade to God’s glory as His children, that is, as dwelling places of the Holy Spirit. But all of this is not a given. It demands a human response. God’s redemptive act in the cross is now a human task. We become more attuned to the Holy Spirit in our midst when we participate in the redemptive action of the cross by sacrificing for others through acts of loving kindness and mercy.

What about the Holy Spirit in Islam? And all those other things? The divinity of God? The lordship of God? Creation? Redemption? What does Islam say about all that? Let’s start with a hadith. What is a hadith? The Qur’an is the speech of God. A hadith is a saying of the Prophet Muhammad: a prophetic saying. There are specialists in the science of hadith who seek to determine whether a saying was soundly transmitted from the Prophet Muhammad in order to ascertain whether it is his own words or words attributed to him. Hadiths are ranked according to the soundness of their transmission. Can they be traced back to Muhammad? Some are considered sound, others questionable. The hadith corpus is vast and provides “the meat and potatoes” of the Muslim way of life. Do they say anything about the Holy Spirit? Of the thousands of hadiths, one reports that the prophet made the following statement: “The holy spirit (rūḥ al-qudus) inspired (literally, spat in) my soul (rū‘ī): ‘A soul does not die until it completes its provision (rizq), so do well in seeking [it], and do not let any delay in your provision lead you to seek it through acts of disobedience to God—for what is from God is not obtained except through [acts of] obedience.’”

As all hadiths, this one has a message. It calls people to earn a livelihood but not if it entails disobedience to God, that is, to the will of God as spelled out in shari‘a. But the hadith also confirms that Muhammad did not concoct the message. It was delivered through the inspiration of the holy spirit. What is going on here?

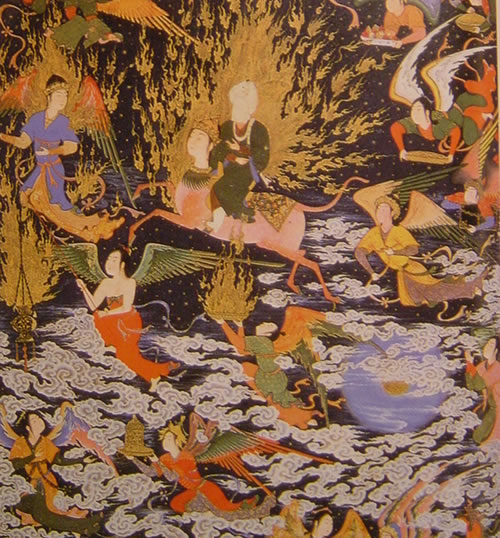

For Muslims, this holy spirit is not a divine person, and it is for this reason that I do not put it in capitals in order to distinguish it from the Holy Spirit as Christians know it. Here, as in general in Islam, the holy spirit refers to the Angel Gabriel. This also applies to the Qur’an, which speaks of the holy spirit and of God’s spirit. First, what does the Qur’an mean by God’s spirit? In some verses, the Qur’an speaks of God breathing His spirit into human beings to bring them to life. (Special reference is made in this regard to Adam and Jesus, the point being that Jesus is no different from Adam: merely human.) In other words, God’s spirit is the animating principle of human life. The human is made up of material substance that is brought to life when God’s spirit is blown into it. Second, what does the Qur’an mean by the holy spirit? Muslims understand this to be a reference to the Angel Gabriel. A few verses state that God supported Jesus with the holy spirit, that is, the Angel Gabriel. This is not about redemption. It is about the status of Jesus as a prophet. Like other prophets, he receives support from the Angel Gabriel. The Qur’an speaks of the spirit in several places in this sense: the spirit in the company of angels as conveyors of God’s message. In other words, it is the angels who mediate the spirit of prophecy between God and His specially chosen (and angelically supported) servants. Along these lines, another hadith notes that when the prophet bowed down in prayer, he would sometimes say, “Glorified (subbūḥ) and Holy (quddūs) is the lord of the angels and the spirit.” In sum, the spirit here is the spirit of prophecy as mediated by angels, a theme that the Qur’an shares with other biblical material of the apocalyptic type. Don’t worry if you don’t know anything about apocalyptic literature. The point is that prophets are inspired. They don’t make things up. That doesn’t make them temples of the Holy Spirit. It simply means they are inspired with the spirit of prophecy to speak a message from God to the people. And the spirit inspiring them is understood as a spirit that angels mediate, especially the Angel Gabriel.

In Islam, then, the holy spirit is the Angel Gabriel who mediates between God and prophets. So, the holy spirit in Islam is not the Holy Spirit in Christianity. The holy spirit in Islam is not about the Holy Spirit as poured out onto creation, making all things new. It is therefore not about redemption, but it does have a role in guiding humanity. After all, it mediates the message of God to humanity. What is God’s message to humanity? To keep it short: We are to live life in full knowledge that in the end we all return to God. We should thus act accordingly. So, there are differences: The holy spirit in Islam is not about humans as temples of the Holy Spirit. The Qur’an does talk of “a new creation” (khalq jadīd), but it is not what Christians mean by “new creation,” namely, life in the Holy Spirit. In the Qur’an, the phrase is used to affirm the power of God in the face of naysayers: You might deny the resurrection of the body, since the body clearly decays and returns to dust, but God has the power to reassemble this dust as a new creation, that is, to refashion it in bodily form. The point is that the body can be brought to life again by God’s power. He created once. He can create again.

So, there are differences. But there are also similarities. We all return to God in the end, Christians and Muslims are agreed on this, and God gives us guidance to journey towards our ultimate end in God as His slaves rather than as slaves to this fleeting world we inhabit for such a brief period of time. And while Muslims do not quite speak of the resurrected body as redeemed and glorified, they do speak of it as transformed for its eternal state. In this world the limbs of our bodies do not last (fānī), but in the next they are eternal (bāqī). Is this the glorified body that Christians speak of in reference to the resurrection? It’s not the same, but there is something similar.

What we have learned so far is that it is not quite right to speak of the Holy Spirit in Islam. The holy spirit is part of the mix, but not the Holy Spirit. Still, simply because the phrase is not used in Islam as it is in Christianity does not mean the concept is not there. In other words, is there in Islam the conceptual equivalent of what Christians mean by the Holy Spirit? Do Muslims speak of spiritual realities in a way that resembles the Christian notion of the Holy Spirit as active not only in creation but also in redemption? Do Muslims not believe that God creates and redeems? Muslims certainly do believe God is creator and lord of all. Do they believe that God redeems us in our sinfulness? Do they believe He redeems infidels? Christians believe God redeems us in our sinfulness, but do they believe He redeems us in our unbelief?

Let’s first get some insight on the concept of lordship in Islam. Again, the divinity of God is one thing, the lordship of God another. As Christians, Muslims understand the lordship of God in terms of His actions, which fall under three broad headings: creation, governance, and provisioning. God creates. God governs His creation. And God provisions it with what it needs to flourish. And creation is not simply about materiality. It is also endowed with spirituality. The mystical heritage of Islam speaks of spiritual senses. We have physical senses. They exist so that we might know the physicality of life. We also have a rational faculty. It exists so that we might accept the knowledge that comes from compelling arguments, and we can even know of God by means of the rational faculty. But it’s one thing to know of God, another thing to know God. Islam’s mystics speak of seeing God. By that they mean that it is possible to know—and not merely know of—God. You have spiritual senses, so use them!

Muslims have different views on what it means to see God. Some say that creation acts as a mirror of God. In this sense, the mystically astute are able to see the image of God reflected, as it were, in the mirror of creation. Whatever seeing God might mean, it requires a spiritual faculty of some kind. The mystics refer to it as one’s inner essence (literally, mystery, sirr in Arabic), which God has implanted in the depths of one’s being. In that sense, it belongs to God more than it does to humans. Along those lines, some note that our sirr is something that God has access to and that He uses to orient us to Him in ways we ourselves might not recognize.

The concept recalls what Christian monks refer to as the apex affectus. They described it in the following way: “Just as a stone pulled by its own weight is naturally drawn down to its own center, so the apex of the affectus by its own weight is carried up to God directly and unmediatedly.” Here, we are speaking of the spirituality of creation. We are not speaking here of what Christians mean by the Holy Spirit in a special sense. The idea, rather, is the human spirit that God has endowed with a penchant for knowledge of spiritual realities, realities that cannot be grasped by the physical senses and the mind alone. Here, then, we have something similar to the Christian concept of creation. It is not just a physical reality. More primordially, it is a spiritual reality, and the human being has the capacity to know it as spiritual reality and not only as physical reality. This is particularly true, as seen above, in terms of the inner life. Muslims, too, see it as a boundless realm waiting to be discovered—so long as we don’t push the button! When it comes to creation, Muslims and Christians seem to be very much on the same page in terms of its spirituality.

What about redemption? That’s a tougher question. Do Muslims describe God as redeemer even if not speaking of the Holy Spirit in the Christian sense? Islam does not speak of God as High Priest. Indeed, Islam had no priesthood. There is a scholarly hierarchy in Islam. Muslim societies have religious establishments. There are spiritual brotherhoods with saintly masters. But there is no priesthood in the sense of the office that undertakes acts of redemptive sacrifice on behalf of the people in order to restore them to life with God. (That said, we need more reflection on the sacrifice Muslim families undertake at the Feast of the Sacrifice. The father of the family does act as “priest” on behalf of the household. He slaughters a chosen animal, undertaking a “redemptive” sacrifice that wipes away the sins of the past year. Nevertheless, Muslims would never speak of themselves as priests.) Still, do Muslims not believe that God redeems them from their nothingness, preparing them for eternal life with Him?

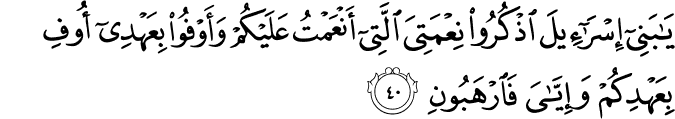

Qur’an 2:40 (Surat al-Baqara): O Children of Israel, remember My grace which I have bestowed upon you, and fulfill My covenant so that I might fulfill your covenant, and have fear of Me.

One can think of the beginnings of Islam as a movement for covenant renewal. The Bible speaks of different iterations of the covenant. There’s the covenant with Noah, the covenant with Abraham, the covenant with Moses and the Israelites, the covenant with David, and the renewal of the covenant under the leadership of Ezra after the Babylonian Exile. For Christians, the covenant is sealed once and for all with the blood of the cross. So, throughout biblical history, there have been covenant renewal movements, and this continued even after the cross as final seal of the covenant. The Church recognizes this: There is always need for covenant renewal. This does not necessarily mean getting people saved (whatever that might mean exactly). The goal is often moral reform, getting people who already believe but who have lapsed to repent and turn to God as the lord of their lives. Such a movement often requires a focus of some kind. If we are to repent and turn to God, where exactly are we to turn in order to encounter God?

Covenant renewal movements often come with specific ideas about the House of God. Where do the people encounter God? In a meeting tent? In a temple on earth? In a heavenly temple? In the Body of Christ? In other words, covenant renewal often involves temple relocation! There is good reason to see the mission of Muhammad as a covenant renewal movement. The text of the Qur’an speaks to the events of his life in Mecca and Medina, but it is also thoroughly rooted in the biblical heritage, as if seeking to renew that heritage for its particular audience in seventh-century Arabia. The covenant is to be renewed through the prophetic message of Muhammad. People are to repent and turn to God. But where are they to turn? Again, covenant renewal often involves temple relocation. The lordship of God will henceforth be closely associated with the Ka‘ba in Mecca. What does that mean for Muslims?

Do Muslims see the Ka‘ba as God’s dwelling place? Not exactly, but it does have a relation to the throne of God, that is, the throne upon which God is present. The throne of God stands metaphysically above the Ka‘ba. Angels circumambulate it. And in imitation of them, believers circumambulate the Ka‘ba. So the Ka‘ba is the place where one can be close to God, but it is not quite the place where God dwells amidst His people as He does in the ancient temple of the Israelites.

Interestingly, there are early reports that tie the building of the Ka‘ba with the term that Jews use to refer to the divine presence dwelling amidst the people. The term in Arabic is sakīna. We will explain its association with the Ka‘ba in a moment. First, a word on the Ka‘ba: God sent it down with Adam, but in time its location was forgotten and all trace of it lost until Abraham and Ishmael were sent to rebuild it. But how did they discover its original location so as to know where to build it anew? Some reports say they were instructed by the sakīna. The reports say that the sakīna descended in a thick cloud; that it spoke to Abraham; and that it instructed him to build the Ka‘ba over it (i.e. over the sakīna). Thus, according to these reports, the sanctuary in Mecca has a close association to the sakīna. But what is the sakīna?

Reference needs to be made to the rabbinical heritage. (After all, one cannot overlook the relation of Islam in its beginnings to the Jewish communities of the day.) Rabbis have long referred to God’s presence amidst the people as the shekhina, whether in the meeting tent at the time of Moses or in Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem or in the synagogue after the destruction of the second temple. But the rabbis did not always agree on the nature of the shekhina. Some saw it as God’s very essence dwelling amidst the people. Others saw it as a power from God—but not God’s very essence. Still others saw it as a light that is present to the people when they gather to pray and absent when they disperse. But there were those who could not accept this. If the shekhina is present only when Jews pray, wouldn’t that make God’s presence depend on human activity? Does God cease to be present when Jews stop praying?

Such debates aside, the shekhina has long been identified in the rabbinical heritage (and also in the Jewish mystical heritage) as God’s presence amidst the people. Is this what is meant in the early reports on the building of the Ka‘ba in Mecca, reports that tie its location to that of the sakīna? No, it’s not quite the same. In none of these reports is the sakīna described as God’s presence. The point of these reports, then, is not to describe the Ka‘ba as God’s dwelling place amidst the people. It is rather a way to garner legitimacy for the Ka‘ba by grounding it in a concept familiar in the rabbinical heritage. It seems some Jews may have questioned the attempt to replace the temple in Jerusalem—in the direction of which Muhammad initially prayed—with the Ka‘ba. Once the legitimacy of the Ka‘ba was established over such objections, Muslims, it seems, gradually stopped talking of the sakīna in terms of a particular entity and a particular locale.

Still, for Muslims through the centuries until today, the sakīna is something sent down by God. What does it mean to speak of something sent down by God? It’s not just about creation, that is, our status as creatures brought into existence from nothingness by the power of God. It’s more than that. It gets sent down onto a creation that already exists. Is it Islam’s version of God’s redemptive activity? Does God send down the sakīna in the same way Christians understand the outpouring of the Holy Spirit onto creation?

It’s not the same, but there is a distinct echo. The Qur’an speaks of God’s sakīna—God’s sakīna! It gets sent down upon the hearts of believers (often but not always in a battle context) to assure them of God’s support. One can think of it as a special grace—Muslims might not phrase it that way—that gets sent down by God upon believers to give them peace and tranquility in times of tribulation and confusion. Islam’s scholars speak of it as a gift (mawhiba) from God, and it imbues believers with qualities akin to what Christians refer to as the gifts of the Holy Spirit (as listed, for example, in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Isaiah in reference to King David): For Islam’s scholars, the sakīna is light in the heart that discloses the truths of the faith. It is life that renews spiritual awareness after a period of neglectfulness. It is strength to speak the truth and a power to help one do the right thing. And it gives one spiritual pleasures, pleasures associated with actions in obedience to God in compensation for the pleasures of disobedient actions that one abandons upon turning to God. The sakīna is not a divine person, but it is something that descends from God onto the hearts of the faithful. It is a gift from God to help believers maintain their beliefs and morals–their integrity–in the face of temptations. It is not redemption, but it is divine help of a kind.

Islam’s scholars generally make no connection between the sakīna and the building of the Ka‘ba in Mecca. Again, that connection fell by the wayside once it served its purpose. However, Islam’s scholars have long associated the sakīna with inspired speech. What in the world is inspired speech? Islam’s scholars are careful to distinguish it from prophetic speech. That ended with the Prophet Muhammad. But prophetic speech is only one kind of divinely inspired speech in Islam. Was the community of Muslims to be deprived of inspired guidance simply because prophetic speech had ended? The issue is not without controversy among Muslims themselves, but Islam’s scholars recognize that the sakīna descends upon the hearts of the righteous and may inspire them to speak for the edification of the faithful.

Thus, through the tongues of the righteous, the sakīna reminds the community of the truths of its faith and morals; it animates the hidden depths (literally, mysteries, asrār) of one’s being; and it resolves theological ambiguities that have long baffled the experts. In short, the sakīna, working through the community’s righteous members, helps to strengthen its commitment to God. The person inspired by the sakīna speaks without thinking and is not in control of the words issuing from his mouth. Why does the sakīna descend upon one person as opposed to another? It descends, the scholars say, as a result of a person’s devotion to God, to God’s messengers, and to God’s slaves (i.e. the community of Muslims).

It is, then, those who are righteous who know the sakīna. Their lives are animated by it. It turns life for God into a pleasure rather than a burden. And through them, it encourages the rest of the community. Is there not a resemblance here to the Holy Spirit? Saint Augustine said that it is due to the hand of the Holy Spirit touching our souls that a delight (delectatio) takes shape within us, a delight in God as the supreme good; and that such a delight in turn begets a love for God as the source of all goodness. Is this the pleasure that Muslims know when the sakīna descends upon their hearts? If so, this would suggest some relation between the sakīna and the Holy Spirit. How are we to understand it?

Perhaps the rabbis can help us see the connection. How ironic that we need to turn to the rabbis to grasp the historical details that bind Christians and Muslims in spiritual kinship. It makes sense. After all, the Jewish heritage is strongly at play in both Christianity and Islam. Let’s begin with a hadith. This hadith states that when a people gather in one of the houses of God to recite scripture, to study it together, and to recall God, the sakīna descends upon them, mercy engulfs them, angels surround them, and God mentions their names in His heavenly court.

So, as Christians experience the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in a special way when they come together to celebrate the Eucharist, so, too, Muslims experience the descent of the sakīna primarily as a result of the acts of devotion they undertake. This makes sense: Both Christians and Muslims can claim a share in the legacy of the ancient temple of the Israelites. The two faith traditions are not the same. The descent of the sakīna does not proceed from any act of redemptive sacrifice by God on behalf of creation as the Holy Spirit does for Christians.

Still, the two—the concept of the sakīna and the concept of the Holy Spirit—could be described as distant cousins since they both bear a relation to the divine presence (shekina) of which the rabbis speak, dwelling amidst the people in the ancient temple of the Israelites. For Christians, the cross fulfills what the ancient temple symbolized, namely, God’s presence amidst His people, now as the Holy Spirit working to make all things new for life with God. For Muslims, this hadith recalls rabbinical ideas about the synagogue where, after the destruction of the second temple at the hands of the Romans, the faithful experienced the shekhina through communal prayer and study of the Torah. How are we to understand all this? The spiritual legacy of the ancient temple is like a majestic river. It has its main course, but it also has its varied branches. For Christians, the main course is the Holy Spirit, but it would be no compromise for them to see in the sakīna something that gives Muslims a share in it. Indeed, they would be denying their own legacy if they did not admit that it is so.

There’s one last point to discuss. We need to think more deeply about how things get sent down from God. Is it God who takes the initiative? Or does our pious activity and moral righteousness bear a causal relation to our experience of God’s mercy? Muslims and Christians both have important perspective to offer. There is the question of what gets sent down. Is it God’s very essence, the Holy Spirit as divine person? Or is it divinely inspired power of a kind that encourages us to persevere on the straight path despite all adversities?

Christians and Muslims have different viewpoints about the nature of what descends upon them. They can enrich one another as each listens to how the other comes to know God and not only know of God. But the differences remain. In addition to the question of what gets sent down, there’s another important question. What causes God to bestow spiritual (and not merely material) gifts upon His creation? What causes God to send down His special grace onto creation? Here, too, Christians and Muslims have much perspective to offer one another, but differences remain.

The differences are due in part to the varied ways in which the two faith communities understand the fall (of Adam and Eve, i.e. the human being) and its consequences. For Christians, humanity may not be depraved, but it is fallen. It cannot know life with God without God taking the initiative. In other words, humans are unable to turn to God without a sign of His love, that is, without their hearts being touched by God’s prior manifestation of His loving kindness. But once humans know what God has done for them, they can participate in His work through acts of worship and acts of loving kindness of their own. Their works are seen as participating in—not causing—life in the Holy Spirit.

It’s a little different in Islam. There is a hadith that speaks of God descending to the lower heaven in the last third of every night (so that believers might petition Him). And there’s a report that speaks of God’s hand touching the Prophet Muhammad between his shoulders in a way that had a deeply consoling effect on him. However, in general, Islam’s scholars speak of a causal relation between human action and things that get sent down from God–His mercy, His forgiveness, His sakīna. In other words, human actions matter in the divine economy. They shape the way humans experience God’s spiritual gifts. (This connection between human actions and human experience of God’s spiritual gifts has been lost sight of in the Christianity of the post-Enlightenment West.) In this sense, redemption is in our hands. God has given us the means to work towards our salvation … but that means we have to work towards it! For example, Islam’s scholars say that when we pray, past sins are wiped away, so better to pray than to wait on God to give you the quick justification fix. Again, the point is that human actions matter in terms of the human experience of God’s spiritual gifts. Of course, this is not quite what Christians mean by redemption. Redemption is God’s initiative apart from human effort (although it does demand a human response). Indeed, for Islam’s scholars, it is not quite clear that humans need to be redeemed. Islam has a different understanding of the fall and its consequences.

To be sure, Islam’s scholars recognize that humans are not perfect, but they have guidance from God, the message of the Qur’an above all. So it matters what believers do. One can place one’s hope in God, but what one does leaves its impact on the spiritual tenor of life. You may go off to study the Qur’an with fellow believers, but if you do so without first seeking forgiveness for your offenses (especially those committed against your relatives), then your presence at the study session will act as a block on the descent of God’s mercy. Or if you persistently insult others, a bad spirit rather than a good one will descend upon your soul. In other words, our actions are spiritually causative. Act kindly towards others, and God’s forgiveness will fall on you. Are we splitting theological hairs? Christians talk about participating in God’s mercy towards creation, Muslims about causing it through our own behavior. In the end, it may be enough to say, “Believe in God. Act Righteously. And God will be with you.”

Now I need a coffee.

I had the opportunity to test my ideas on this topic at a number of universities. For the invitations to do so, I thank Father Richard Liddy at Seton Hall University, the Faculty of Religious Studies at McGill University, Professor Shari Lowin at Stonehill College, and Professor Jamie Schillinger at St. Olaf College.