How Did You Live His Death?

by Paul L. Heck

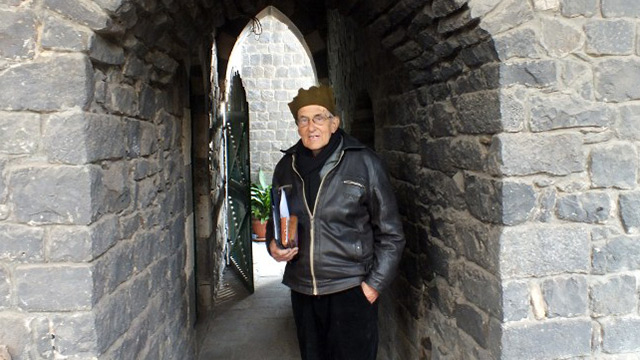

Today, a dear friend, a woman from Syria who lives with her family in a village in Switzerland not far from Geneva, asked me a question on Facebook, “How did you live the death of Franz?” She was referring to Father Franz Van Der Lugt, shot on April 7, 2014 at the residence of the Jesuit Fathers in Homs, Syria, seventy-five years of age.

His killing drew international attention. The media wanted to know of this saintly man who had spent the bulk of his life serving the people of Syria. The media wanted to know of this courageous person who had chosen to stay in Homs during the long siege of the city, the only priest to do so. He ministered to the needs of people in distress and even starved alongside them as their food supplies dwindled.

His killing drew international attention. The media wanted to know of this saintly man who had spent the bulk of his life serving the people of Syria. The media wanted to know of this courageous person who had chosen to stay in Homs during the long siege of the city, the only priest to do so. He ministered to the needs of people in distress and even starved alongside them as their food supplies dwindled.

All of this is important, but the real story lies in my friend’s question, “How did you live the death of Franz?” The question itself sounds odd.

Perhaps it only makes sense to those who knew Franz deeply. His death produced a strange joy in us. There was initial shock, but it straightaway changed to joy at the sense of his spirit entering into us and strengthening us. He had not simply died for a noble cause. Nor was it the memory of his life that we found consoling in death. A spirit passed from him to us. It was more than a desire to bear his spirit. It was a power enabling us to do so. What do I mean? The spirit of Franz was a spirit of self-giving, of love, of service, of openness to all. His was the spirit of Christ. We had witnessed it in his life and now experienced it more concretely in his death. We received it deep into our souls.

Perhaps it only makes sense to those who knew Franz deeply. His death produced a strange joy in us. There was initial shock, but it straightaway changed to joy at the sense of his spirit entering into us and strengthening us. He had not simply died for a noble cause. Nor was it the memory of his life that we found consoling in death. A spirit passed from him to us. It was more than a desire to bear his spirit. It was a power enabling us to do so. What do I mean? The spirit of Franz was a spirit of self-giving, of love, of service, of openness to all. His was the spirit of Christ. We had witnessed it in his life and now experienced it more concretely in his death. We received it deep into our souls.

I’m not supposed to speak this way as a scholar. I speak of a lived experience. His spirit came to us not as a nice idea but as a force flowing into us. What language do I have to describe it? To what would I liken it?

It was a taste of the new life that the disciples experienced at the resurrection of Jesus. It was a transformative experience. I think I now better understand what they lived. It was not merely amazement at the resuscitation of a dead body. More precisely, what they lived was the power of his spirit. They had witnessed it in his life, a powerful spiritual presence itself. But they were taken by it even more forcefully at his resurrection.

How did I live the death of Franz? I’m certainly not alone in what I say. I’ve been struck at the myriad of responses to his death on Facebook. His death, strange as it might sound, has been a source of new life for many. One post captures it in a sentence. It’s a photo of a man—Gabi Bahdi from Aleppo—squatting at the grave of Franz in Homs. Underneath it is the caption, “True, your body is under the ground, but your spirit remains living in us.”

The gift of the Holy Spirit: This is how I would name it. I’m not speaking theologically. I am speaking of the lived experience of many people. It is not simply a memory of a saintly and courageous man. It is not simply a desire to continue his good works now that he is gone. It is a gift from him to us, a gift of life in death. It is his saying, “Here is my spirit. I pass it on to you.”

His death has given us a sharper sense of how the Holy Spirit works in the world and, more specifically, how it passes from one generation to the next. It is not a theory. The process is not abstract. It is actually very concrete. The spirit of Christ was alive in Franz. He passed it on to us in his life but even more powerfully in his death. The spirit of Christ passed to his disciples, then to the next generation, then to the one after that, then to Franz, through the centuries until today. It is a process that takes place in bodies, spiritually enlivened bodies.

What does it mean to be a martyr? I’ve studied martyrdom for some time. I teach a course on it. It is a complex phenomenon. Its many sides range from the political to the cultural. It is a willingness to die for a cause. The death may or may not be self-inflicted. It may or may not involve the killing of other people. To understand a particular case, one has to study a host of factors: the mindset of the martyr, the political context, and the community’s attitude toward martyrdom. There are martyrs for the faith, martyrs for justice, martyrs for the nation, martyrs of conscience, battlefield martyrs, martyrs for freedom and dignity. The list is not short. However, in all cases the death of the martyr invigorates the community and strengthens its sense of purpose. Can one say that the spirit of the martyr in all types of martyrdom passes on to the community at death? Perhaps. But there are different kinds of spirit at work in the world. What kind of spirit does the martyr transmit to others in death? It is the spirit to which the martyr bore witness in life. Is it a loving spirit? Or is it a fighting spirit? Is it a spirit of forgiveness or a spirit of vengeance? Is it a spirit of friendship or of enmity? Is it a spirit of truth or a spirit of self-interest?

I pose the question not to lay down categories but rather to encourage discussion of the spirits that guide us in life and that we pass on to others in death. Here, we are considering the case of Franz Van Der Lugt. He had his foibles. Some did not like his style. But it cannot be denied that he was a man of peace. He was committed to the people of Syria irrespective of their religious affiliation. He cared for their souls, the growth of their souls above all. All his activities brought people together, not simply to bring them together, but to create a way for them to grow together towards God. He opened up the residence of the Jesuit Fathers in Homs to families unable to flee the violence, Muslim and Christian alike. Together, they became a witness to cross-religious solidarity in a nation at war with itself. This was the crowning achievement of his life. It is no accident that Muslims come to pray over his grave in their way.

What does this mean? In life, he drew out the true character of the people of Syria, and this continues in death. Indeed, he has left a legacy to the people of Syria in a series of short talks he gave during the siege of Homs. In them he speaks of the true character of the people of Syria in terms of solidarity. The word in Arabic is mushāraka (second syllable long). The talks are available in Arabic on YouTube. In what follows, I’ve gathered together excerpts of these talks as a way to convey something of the spirit at work in Franz in relation to the society in which he lived.

He begins by describing the Syrian people in terms of mushāraka. “The people love to share with others what they love. A mother never cooks only for her children. Half is for others. The act is never planned in advance but is spontaneous. When we visit people, they do not have a lot but always save the best for the guest. They speak of their pain but always ask how you are. They want to share in your life. Amidst the severest suffering, they remain open to others and eager to share with them.”

He continues, “We see this in daily life but especially on the hikes when we pass through fields and gardens. The owners invite us to eat from their fruit. They are not at all annoyed but happy to share their blessings with us. They do not think about being paid. They are not relieved when we leave, nor do they wish we had not come. It is natural, brotherly, spontaneous mushāraka. It is on account of this spirit of mushāraka at the heart of the Syrian people that I have come to love them.”

One could add that it is for this reason that he chose to remain with them when it would have been easy enough for him to flee to safer places. In a clip in French, he notes that the residence of the Jesuit Fathers is located amidst two neighborhoods in the old city of Homs, Boustan Diwan and al-Hamidiyya. Prior to the violence, the two neighborhoods were home to fifty thousand Christians belonging to eight different denominations. Only seventy-five individuals remain at the time the clip was recorded. They lived in solidarity, helping one another and ensuring no one was left in need of food or medicine. The residence of the Jesuit Fathers became a place of hope. The other churches had been destroyed, so the remaining Christians would come together there on Sundays for Eucharist, on Wednesdays for a communal breakfast, and for varied gatherings throughout the week. As Franz notes, “We do not know what will happen, but we do know that Syria is suffering, and we experience the suffering, with the hope of new birth.” It is the sense of mushāraka as he had learned it from the peoples of Syrian that compelled him to remain, to participate with them, as he puts it, in all things: sorrow, fear, pain, and death, but also to pass with them from fear to peace, sorrow to joy, death to new life.

Why should these words interest us now? The uprising in Syria was led by desperate youth, pushed to the brink of annihilation by harsh economic conditions worsened by the global recession. It was encouraged by satellite stations in the naïve expectation that it would be over in a few weeks as in Tunisia and Egypt. The regime reacted viciously and will continue to do so until the bitter end. Towns in so-called free areas have attempted to self-govern, but jihadist groups pose a serious threat to the nation. They have been vicious, exhibiting a readiness to kill people solely on the basis of religious affiliation. A vision of future reconciliation is greatly needed, one that extends to rich and poor and to the country’s many confessions.

Franz, sitting on his stool, continues to speak. The bomb blasts nearly drown out his voice at times. Remarkably, he is a model of tranquility. He has more to say about mushāraka. He speaks of the women in the villages of Syria. “When they see us, they call to us to sit and eat from the bread they are baking. They are joyful at this opportunity to offer hospitality and to give freely. They don’t want anything. They’re happy that we’re happy, but it’s not a condition. Their sharing comes from the heart, from a heart that overflows like a spring: spontaneous and natural generosity. If you ask them why they act in this way, they won’t have a response right off, but if you spend time with them, they’ll say to you, ‘The bread belongs to God. We thank God for this bread. We live from it but also give it freely to others because we’re not giving from what is ours. It is God’s. As he gave it to us, so we give it to others.’”

Franz continues, “We ask them why they do this, since we’re many and there may not be enough for their children. One of them said to me, ‘Brother, see this worm in that rock, doesn’t God provide for it? Will he not provide for us? Does God abandon anyone? All goodness is from God, and there is plenty of goodness to go around.’”

Franz now comes to the point. The words of these simple women, he says, contain a spirituality that stands at the heart of every religion. It is at the heart of Islam; the village women of whom he speaks are largely Muslim. In Christianity, of course, the breaking of the bread is essential. “What are we doing when we break bread together? We thank God for it and then give each a share in it as a gift from God. We all eat and become one body, one community. Saint Paul says, ‘Is the bread we break not a mushāraka (sharing) in the body of the Christ?’ By participating in the one bread, we become one body. The Gospel of John says, ‘This one bread is the Christ, the bread of God, the bread of life that has come down from heaven.’ We thank God for this bread, and by participating in it, we become one body. It is by our unity that our mushāraka with Christ is measured.” Franz explains: “There is something true in this: We see how God gives us bread through the hands of women and how God gives us the body of Christ as the bread of life: God’s bread that has come down from heaven, the bread of love. (Gunfire intensifies in the background.) To the extent we live life in its depth, we approach the essence of every religion and discover that what is at the heart of religion is the very thing that is at the heart of life.”

I’ll stop there for now. I may have more to say in the future. The meaning of his death continues to unfold. He has left a vision for Syria to pursue when it comes time for the nation to reclaim its soul and heal its wounds. His death serves as a reminder of the truth of the peoples of Syria and a sign of hope for the nation’s future. More profoundly, his death acts as a conduit for the Holy Spirit to be present in Syria in the people who experienced in his death a source of new life. His death will only strengthen the spirit of mushāraka in Syria. In hindsight, this should not have surprised us. After all, as a priest, every time he celebrated the Mass, Franz would repeat the words, “May the fellowship (mushāraka) of the Holy Spirit be with you all.” His death, as his life, offers insight into the ways of the spirit.